Significance of the Site

The Sulphur Creek Trestle Battle Site is considered significant at the local level under Criteria A for Military History as the location of an 1864 Civil War battle in Alabama between Union troops, including United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.), and Confederate forces under the leadership of Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest (Figure 1). While Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman (Figure 2) occupied Atlanta on September 2, 1864, thereby completing an important part of his march across Georgia, he and his men were still reliant on supply lines that came through Tennessee and North Alabama until the March to the Sea began in November. The engagement at Sulphur Creek Trestle was an important part of the Confederate effort to break these lines before the bulk of Sherman’s force left Atlanta. The engagement reveals much about both Union and Confederate tactical decision-making during the later phases of the Civil War. Additionally, the battle fought at Sulphur Creek Trestle Battle Site is a textbook example of the battle strategy and tactics that made Gen. Forrest such a formidable opponent to the Union army. The period of significance is September 25, 1864—the day the battle took place.

The Sulphur Creek Trestle Battle Site is also considered significant at the local level under Criteria D. Future archeological examination of the site has the potential to contribute new historical information related to troop position and movement.

Criteria A: Military History

On September 25, 1864, Confederate troops under the command of Gen. Forrest attacked Union forces guarding the Sulphur Creek Trestle Bridge. The ensuing battle resulted in the deaths of 200 Union and 40 Confederate troops. Gen. Forrest took the remaining 820 Union troops prisoner. The Sulphur Creek Trestle Bridge, the largest bridge on the Nashville & Decatur line, was burned, making rail travel from Nashville to Decatur impossible. The previous day, September 24, Forrest and his men had successfully defeated Union forces at Athens, Alabama, and had destroyed an additional section of the Nashville & Decatur railroad line. Both conflicts were part of a campaign to destroy Gen. Sherman’s supply lines before he left Atlanta in the fall of 1864. The failure of the Confederate forces to attack Sherman’s lines earlier in the summer because of problems with the Confederate command structure and disagreements over the necessity of carrying out the attacks (as Forrest had urged) meant that the victories at Athens and Sulphur Creek Trestle came too late to affect Sherman’s efforts in Atlanta but the victories did, in part, influence Sherman’s decision to live off the land as his men marched east to Savannah as his supply lines were vulnerable to Confederate attack. The expanded boundaries of the Sulphur Creek Trestle Battle Site include intact landscape elements that lead to a further understanding of Forrest’s tactics and his use of topography to defeat Union forces.

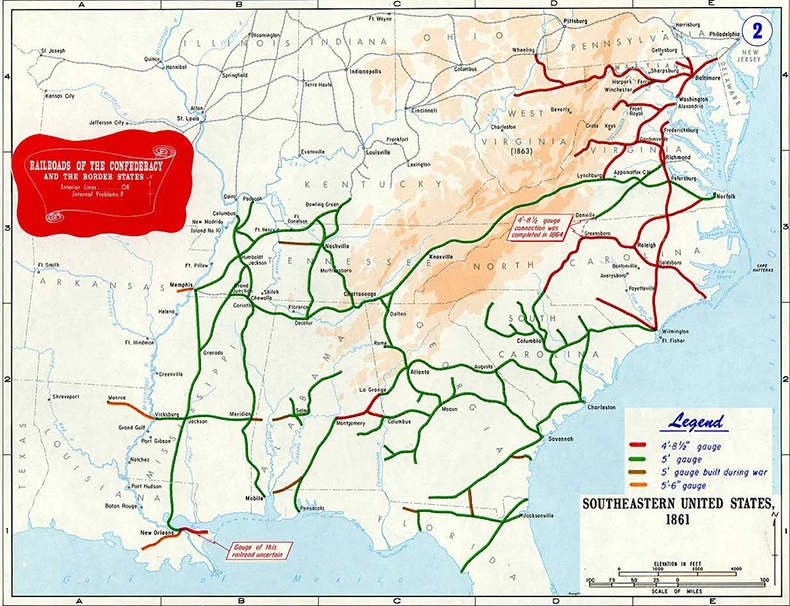

In late 1863 Sherman was making preparations for his Atlanta Campaign, which would eventually climax with the capture of Atlanta in September of 1864. Before setting out on this campaign Sherman realized the necessity of securing his vital supply lines between Nashville and his army located in the vicinity of Chattanooga, Tennessee. Because his position was far removed from Union supply lines and stores, Sherman had to rely on a long and rather vulnerable network comprised of rivers and railroads (Figure 3) to get supplies to his men. Some Confederate leaders recognized that if this network could be compromised, Sherman’s efforts to take Atlanta might be at risk.1

In an attempt to prevent Confederate forces from breaking his supply lines, Sherman devised a comprehensive plan that included the use of U.S.C.T. and other units to guard rail lines. Additionally, he developed an improved telegraph system that would allow for reinforcements to be shifted from place to place in support of one another along the rail lines as needed.

Figure 3. Railroads of The Confederacy and Tthe Border States. Courtesy US Military Academy West Point.

The Sulphur Creek Trestle Fort, located one mile south of Elkmont, Alabama, in Limestone County, was a significant part of this line. The men stationed there guarded the largest railroad bridge on the Nashville & Decatur Railroad. The fort, a square 300 X 300-foot redoubt with four corner bastions and an interior powder magazine, was built on a ridge reaching out into Sulphur Creek valley. The earthwork walls were built upon a line of dirt filled wicker baskets, which were strengthened with logs that were then cut through with embrasures for artillery pieces.5 The Decatur & Nashville line was essential to Sherman’s efforts as it moved supplies arriving in Nashville along the Cumberland River southward to Decatur, located on the banks of the Tennessee River. In Decatur the line connected to the Memphis & Charleston line, which ran east to Chattanooga. Supplies then could be moved into Georgia.6 As Sherman fought through north Georgia during the spring and summer of 1864, citizens of the state could not have failed to notice the strange markings on the railroad boxcars as they passed by. Northern supply trains bearing cars marked “Delaware and Lackawanna” and “Pittsburg & Fort Wayne” were symbolic of the mass rail effort Sherman was making. The raw statistics illustrate the significance of both the Nashville & Decatur and Nashville & Chattanooga railroads to Sherman’s campaign. Between November 1, 1863, and September 14, 1864, a period that covered Sherman’s drive on Atlanta, the line had brought 40,000 sick and wounded back to Nashville and returned 50,000 veterans to Sherman’s commands, in addition to moving a river of food, ammunition, and supplies.7

The Nashville & Decatur railroad line was guarded by an infantry division under the command of Maj. Gen. Lovell H. Rousseau, which included brigades under the command of Gen. Robert Granger (Figure 4) at Decatur, Alabama, another under Gen. James C. Starkweather at Pulaski, Tennessee, and a third at Columbia, Tennessee, under Col. W.B. Sipes.8 Col. George Spalding commanded the cavalry belonging to the Department of the Cumberland which included units formed from Tennessee Unionists and soldiers from Indiana. Most of the regiments within these brigades were inexperienced. They were relatively new soldiers and had not participated in any large engagements. Despite their shortcomings, Sherman expected these troops to defend against any potential threat, including Forrest. Around the time he was developing his supply line network, Sherman stated Forrest was “the ablest cavalry general in the South” and urged that “he should be hunted down if it cost ten thousand lives and bankrupts the Federal Treasury.”9 Manning the Sulphur Creek Trestle Fort during the ensuing September 1864 battle was the 2nd Tennessee Union Cavalry, part of the 9th Indiana Cavalry, and the 111th U.S.C.T.

The Battle of Sulphur Creek Trestle represents the first major engagement involving United States Colored Troops in north Alabama. Soldiers serving in the 111th U.S.C.T. (Figure 5) fought in close proximity to the plantations where they had previously been enslaved. Their involvement at Sulphur Creek Trestle represents a growing effort on the part of the Union to enlist former slaves across the south to serve in both combat and support roles in the later phases of the Civil War.

Prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, Limestone County, Alabama, was home to thousands of slaves who had worked the large cotton plantations in the area. These plantations had relied upon the Nashville & Decatur railroad as well as the Tennessee River to convey cotton to locations across the South. The 1860 census had found 60 percent of the county’s residents were black slaves—8,000 of the 15,000 residents—and the slave owners feared what would happen if the war came close to home and their slaves gained access to weapons.10 After the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863 and the formation of the Bureau of Colored Troops in May of 1863, the active recruitment of African-Americans began in Alabama. While southerners tried to prevent the widespread recruitment of their former slaves, telling them that they would not be paid, that they would be mistreated by the Union forces, and, in many cases, by resorting to violence, many former slaves willingly faced these risks to join the fight for their freedom.

Agents who accompanied Union cavalry expeditions around the town of Athens, located in Limestone County, began recruiting black troops in north Alabama, though they often found that black soldiers in uniform were more successful at recruiting the former slaves than white agents11 Three hundred black men were recruited for the 17th U.S. Colored Infantry in 1863.12 An Official Records report concerning the enlistment of black troops states that by, “February 1864 there were 237 recruiting agents across the mid-South and that they had enlisted 7,500 black troops,” many of whom came from north Alabama.13

Figure 6. U.S.C.T. on Parade in Tennessee. Source: Library of Congress

In the spring and summer of 1864, some Confederate leaders realized the very precarious position of Sherman’s long supply line and the important effects that breaking the line could have on Sherman’s campaign. In April of 1864, Forrest communicated with Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, commander of the Army of Tennessee, about the possibility of attacking Sherman’s supply lines. “Forrest himself on April 6 had written Johnston to suggest a mass raid by the cavalry of both departments on middle Tennessee. Then on April 15 Forrest suggested to [Jefferson] Davis that his and [Stephen D.] Lee’s cavalry be sent to break up Sherman’s line of communication in middle Tennessee and Kentucky.”15 Despite the possible benefits this action would bring to the Confederate forces, President Jefferson Davis refused to authorize it, fearing what might occur if so many troops were sent to attack Sherman’s reinforced railroad supply lines in central Tennessee with a Union cavalry force looming at Memphis. The Confederate president insisted that any potential expedition by Gen. Stephen Lee and Forrest would expose Alabama and Mississippi to seizure and potential loss of the iron and munitions areas located there.16 Another attempt in May to organize an attack on Sherman’s supply lines was met with more resistance by Lee himself, after Johnston had made direct inquiries to Richmond about a potential cavalry attack using his forces. “Though only 4,500 Federal Cavalry were reported to be at Memphis, and Forrest reported his two divisions alone boasted 9,220 effectives, Lee on May 18 reported to Richmond that he could not assist Johnston. He did this despite his admission to Forrest on May 20 that his intelligence indicated the railroad between Nashville and Stevenson was weakly guarded, and that 3,500 troops would be enough to do the job.”17 It is significant to note that Lee also had about 5,000 other cavalry troops in his department (North Alabama, North Mississippi, and West Tennessee), including Forrest’s troops, which were performing garrison duties in areas of Alabama not threatened by attack. By June and July of 1864 Forrest was given the task of stopping the continual Union raids into Mississippi.

Figure 8. Navy Colt Revolver. Forrest's troops carried a pair of Colt revolvers. Courtesy wikipedia.org.

Figure 7. Short barreled Enfield rifle. This was tne primary rifle of Forrest's troops. Courtesy wikipedia.org.

By the end of July and beginning of August, a number of events were occurring simultaneously that further prevented a coordinated attack on Sherman’s supply line. The first was that Johnston was relieved of his command of the Army of Tennessee in July and during the ensuing command shakeup Lee was transferred to that army, temporarily leaving the Department of North Alabama, North Mississippi, and West Tennessee without a commander. Furthermore, Adm. David G. Farragut initiated the Battle of Mobile Bay on August 5 and Gen. Dabney H. Maury, the commander of the Department of the Gulf, requested Forrest transfer his command to Mobile. However, on September 4, 1864, as Forrest was in motion towards that location, he received a telegram from Maury. The telegram stated that it would not be necessary for Forrest to go beyond Meridian, Mississippi, where he and part of his command arrived on September 5.19 After this development, Forrest immediately sought and was granted permission by his new departmental commander, Gen. Richard Taylor, to organize an attack on Sherman’s railroad supply lines in central Tennessee. This would lead to the engagement at the Sulphur Creek Trestle Fort in Limestone County, Alabama, and eventually would culminate with the capture of thousands of Union troops. While Forrest was in Mississippi in early September 1864, a cavalry raid conducted by Gen. Joe Wheeler (Figure 9) from Gen. Hood’s Army of the Tennessee upon the Nashville & Chattanooga railroad put all Union division and brigade commanders in middle Tennessee on high alert. Wheeler’s raid took place during an important time for Sherman, who was deliberating which course to take next after defeating Hood and taking Atlanta. Sherman’s first option, and the one he first acted upon, was to follow Hood and the Army of the Tennessee back north. The other option was to march through Georgia towards Savannah, which, once taken, would act as a supply base for his army with the assistance of the U.S. Navy. Until this point, Sherman would have to rely on goods moved by rail or live off the land. While Hood may have entertained a hope that Wheeler could materially affect Sherman’s decision making, the young Confederate cavalry commander would disappoint him. “On September 10 Hood received a grossly misleading report from Wheeler in which he bragged about destroying fifty miles of track on the Nashville & Chattanooga railroad and several key bridges as well. By September 14 Hood had learned that Wheeler had re-crossed the Tennessee River at Florence, Alabama, and evidently was preparing for another expedition. What Hood did not know was that Wheeler’s Corps was practically destroyed and that only slight damage had been done to the railroad.”20 One of the mistakes Wheeler had made on his raid was that he chose not to carry any horse artillery. When he encountered the fortified blockhouses and other installations during the raid he was unable to destroy them or to cause much damage to either the Nashville & Chattanooga or the Nashville & Decatur railroad lines themselves.

Gen. Robert Granger’s Brigade located at Decatur, Alabama, was alerted about Wheeler’s raid by Granger’s division commander at Nashville, Maj. Gen. L.H. Rousseau. Rousseau had already reinforced Granger in the late summer of 1864 when he ordered the 2nd and 3rd Tennessee (Union) Cavalry to north Alabama.21 Wheeler also was being constantly pressured by the Union Infantry brigades stationed at key areas along the railroad. “When Granger heard that Wheeler’s cavalry was moving south along the Nashville to Decatur line he had put detachments from the 35th Illinois, 6th Indiana, and 18th Michigan aboard a train at Decatur and headed north. At Lynnville on September 4th the command surprised Confederate cavalry burning a freight train, and joined Brigadier General John C. Starkweather’s (Figure 9) command from Pulaski. Granger pursued the rebels [Wheeler] through Lawrenceburg [Tennessee] and on to Rogersville [Alabama] before giving up chase and returning to Athens on September 8.”22

It was at the time of Wheeler’s raids that Forrest received permission to attack the railroads in north Alabama and middle Tennessee as part of the attempt by Hood to break Sherman’s lines after the Confederate loss of Atlanta. When Gen. A.J. Smith’s division was ordered to Missouri to operate against Confederate forces under Gen. Sterling Price, Granger quickly telegraphed Sherman that that the assignment would free Forrest to raid railroads in Alabama and Tennessee. Sherman responded to this by sending warnings to residents of Florence and Tuscumbia that if Forrest planned to invade Tennessee from north Alabama, both cities would be burned and their inhabitants likely removed north of the Ohio River.23 For obvious reasons, this gesture did not comfort Granger. Both Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, then in Virginia, and Sherman, in Georgia, attempted to calm Granger’s apprehension as to the whereabouts of Forrest. When Granger persisted in his concerns about Forrest and the threat he represented, Sherman replied that the Union high command had “official information” that Forrest had gone to Mobile. The information had come from Grant, who had reported to Sherman on September 10 that he had seen a dispatch from a Mobile newspaper reporting Forrest was in Mobile. Sherman found the information repeated in the Macon newspapers of September 10 & 11 and telegraphed Gen. George Thomas at Chattanooga that “General Granger need apprehend no trouble from any but Roddey, Wheeler, and the parties that have already been in Tennessee.”24 As a result of these false reports, the Union high command did not perceive Forrest as a potential threat. Smith’s division would not have been redeployed to Missouri if either Sherman or Grant thought that Granger’s fears were well-founded. However, both generals were operating off of inaccurate information found in newspapers. Although the use of newspapers for intelligence was common practice during the Civil War, in this case reliance on newspapers rather than official intelligence reports created an opening for Forrest that would not have otherwise existed. Why Granger did not order more cavalry patrols towards Florence is unknown. What is known is that Forrest totally surprised Granger when his forces captured Col. Wallace Campbell and his entire command at Athens on September 24, 1864. After Taylor had approved Forrest’s middle Tennessee raid, Forrest began to make his characteristically detailed decisions concerning the specific cavalry units he would use. “General Buford’s division was quartered at Verona (Mississippi), which included General Bell’s, Lyon’s, and Rucker’s Brigades. General Chalmers was ordered to take command at Grenada of all troops not selected for the expedition. General Forrest made personal inspection of each regiment in order to ascertain exactly its material and component parts.”25 Preparations were also made for transportation of the Confederate force from central Mississippi to northwest Alabama. Orders were given at the same time to repair the Mobile & Ohio Railroad north to Corinth as speedily as possible. Gen. Phillip Roddey, (Figure 10) near Tuscumbia, Alabama, was instructed to repair the bridges east to Corinth and prepare boats for the ferriage of the Tennessee River near Cherokee Station.26 On September 16, Forrest left Verona, Mississippi, on a series of trains with all of the artillery guns belonging to Morton’s and Hudson’s batteries, along with various other types of supplies. The cavalry brigades along with the artillery horses used an overland route. By the evening of September 19, Forrest and his entire command along with four supply trains loaded with subsistence, ordnance, and quartermasters’ stores had reached Cherokee Station in northwest Alabama.27 The next day the men re-shod their horses and made general preparations for the attack. On September 21 the entire command began to cross the Tennessee River a few miles from Cherokee Station. Both Forrest and Roddey’s commands affected a junction at Shoal Creek, near Florence, on September 22, which brought the raiding forces strength up to 4,500.28 Roddey did not participate in the raid due to illness and remained in Tuscumbia. Col. William A. Johnson was given temporary command of Roddey’s troops, who also added Ferrell’s horse artillery to those of Cap. John Morton’s and Hudson’s, which brought Forrest’s highly mobile artillery strength up to 12 cannons.

By the evening of September 23, Forrest and his command were at Athens, Alabama, and had completely surrounded the town and blocked the roads and railroad lines leading out of the area. They acted with such swiftness that Granger, at Decatur, was apparently unaware that Forrest had moved such a large force into his area. “Colonel Campbell, the Union garrison commander at Athens, had tried unsuccessfully to send dispatches to Pulaski, warning Starkweather that Forrest was at Athens in force, apparently intent on destroying the railroad, but one of the messengers had been wounded as he tried to ride through Confederate cavalry now picketing the northern end of town. A second man, attempting to break through the rebel pickets was shot dead.”29 The reason Campbell had to rely on dispatch riders was that Forrest’s troops cut all telegraph lines around Athens leading north to Pulaski and south to Decatur. However, Starkweather did dispatch two cavalry units from Pulaski to the fort at Sulphur Creek Trestle, 11 miles north of Athens, on the day Athens fell. Starkweather, the area commander at Pulaski, received intelligence that this vital installation was threatened and dispatched 300 men of the 9th Indiana Cavalry, and 400 men of the 3rd Tennessee (Union) Cavalry to augment the 300 men of the 111th U.S.C.T. already stationed at the fort.30 By the time Granger became aware of Forrest’s raid, probably early in the morning of September 24, Forrest was convincing Campbell to surrender his strong garrison and the fort located in Athens using a ruse that has been covered by many scholars. While Granger did send a relief force of a few regiments that pressed forward with an attack to rescue Campbell’s garrison, they too were captured by Forrest’s men. By the afternoon and early evening of September 24, Forrest quickly moved to mount the troops he brought with him that did not have horses and distributed other supplies among his command. Gen. John Buford of Forrest’s command and Col. William Johnson of Roddey’s command began supplying their respective troops from the Federal depot with such articles that their men most needed, including 200 men who had marched to Athens dismounted.31 While this was taking place, a portion of Wheeler’s command approached Athens after learning Forrest was there. The 1st Tennessee Cavalry and approximately 200 men belonging to Wheeler’s Cavalry were also supplied.32 Provisions were then made for the destruction of anything of military value and the conveyance of prisoners back to the railhead at Cherokee Station. By 5 p.m. on September 24, the blockhouse buildings, bridges, and trestlework was being burned to the ground and, the prisoners, captured artillery, and wagon train, all properly guarded, were dispatched rearward in the direction of Florence.33 While the Union chain of command in the area realized that an attack was taking place, with Granger probably realizing that it was Forrest, none expected the speed with which it was carried out. Both Wheeler and Roddey had been active in the area just prior to Forrest’s September raid but neither had been as swift or destructive.

At the same time that the prisoners and captured supplies began making their way toward Florence, Forrest moved his approximately 3,500-man cavalry force out of Athens northward along the Nashville & Decatur rail line toward Sulphur Creek Trestle. The soldiers covered eight miles before bivouacking for the night.34 Forrest had ordered that the area be reconnoitered by a detachment of his troops, who soon ran into garrison troops on patrol from the Sulphur Creek Trestle fort. There was a brief skirmish before the Union forces withdrew into the fort’s perimeters.35 Early the next morning, Forrest and his troops closed the three-mile gap between their bivouac and the fort.36 Forrest and Morton immediately began a reconnaissance of the area, including the fort, to determine the best avenue of attack. At first, the fort likely seemed to be in a secure position.

The fort (Figure 11) a square redoubt, with faces of about three hundred feet in length, which had been thrown up on an eminence to the southward, so as to command the trestle and all approaches. This was furnished with two twelve-pounder howitzers, skillfully arranged, to be fired through embrasures (fortified-covered room), sweeping all possible avenues to the trestle; while some two hundred yards in advance on three sides, it was surrounded by a line of rifle pits. And two formidable blockhouses were built in the ravine, at each extremity, so as to command the ravine and prevent a hostile approach to the trestle that way.37

Figure 12. Sketch of view overlooking the Sulphur Creek Trestle and Fort, Limestone County, Alabama.

The first decision Forrest made (Figure 14) was to push the Union troops located in the rifle pits 200 yards on the pFigurelateau northward back into the fort after dismounting Kelly’s and Johnson’s commands. “Colonel Kelly supported by Colonel Johnson (Roddey’s command), was ordered to drive the Federal pickets and skirmishers within the redoubt. Kelly’s men charged the rifle pits, and made the enemy seek shelter after a short skirmish inside the fort.”38 Unlike the units that fought in linear formations in the Civil War’s large battles, Kelly and Johnson’s men moved in a large extended formation toward the fort, constantly firing and moving. Kelly lost a number of soldiers in this advance; however, despite the furious resistance of the defenders, this maneuvering helped Confederate troops gain an advantage, and Kelly was able to place most of his men within 100 yards of the fort.39 After pushing the Union troops back into the fort, Kelly began maneuvering his troops into positions that provided better cover from the infantry, cavalry, and artillery fire coming from the fort. Buford’s command was moved onto the higher elevations a few hundred yards to the west of the fort, giving them a tactical advantage.

Forrest spent the next several hours in light skirmishes, in the course of which he succeeded, with slight loss, in establishing a considerable portion of his force within 100 yards of the breastworks of the redoubt, under cover of the acclivity of the ridge upon which it was built, and some ravines which seamed it.40 Forrest’s dismounted cavalry was constantly moving to better positions closer to the fort while maintaining a steady fire into it. The fort’s defenders were replying in kind with the U.S.C.T using 1863 Springfield rifles (Figure 15) and both Union cavalry units (Figure 16) with Gallagher cavalry carbines (Figure 17). The two 12-pound Howitzers (Figure 18) inside the fort were also in constant action. They were located in bastions in the northwest and southeast corners, which were arranged to sweep all avenues of approach to the fort.41 While this was occurring, Morton was ordered to scout the area and find advantageous positions for his artillery. The young captain reported to Forrest that there were four locations on the hills surrounding the fort in which his artillery could be positioned that were within 800 yards of and commanding the works, from which he might easily explode his shells inside the fort.42 The 800-yards distance is significant because Morton’s artillery would have been 200 yards out from the effective range of the 58-caliber Springfield rifles carried by the U.S.C.T. With the locations for the artillery found and the dismounted cavalrymen in close proximity to the fort, Forrest called for a truce. Maj. John P. Strange was sent forward under a flag of truce. An hour elapsed before he returned with the answer from Col. William H. Lathrop, the fort’s commander, which was a positive refusal43

Figure 16. Union Horse Artillery. Source: Libray of Congress.

After Lathrop’s refusal to surrender, a simultaneous chain reaction of events begin to make the situation desperate inside the fort. Morton was ordered to immediately deploy his 12 artillery pieces in three main positions around the fort on the surrounding hills and begin firing. Two of these locations on the west and east sides of the fort were of higher elevation than the fort and created a situation where the Confederate artillery could literally fire down inside the fort. On the south side of the trestle, Lt. E.S. Walton split his four-gun battery into a two-gun section on the western elevation and fired into the fort from two different positions, aiming at the southern and western faces (Figure 19).44 Morton moved his own four-gun battery armed with 3” Ordnance rifles (Figure 20), including both “bull pups,” to the eastern side of the fort near the brow of the hill above the fort and began firing at the northern and eastern faces.45 Ferrell’s guns were positioned in a somewhat exposed position in a cornfield, within short range of the fort in support of Johnson’s troops.46

As the barrage began, Union troops quickly realized that Forrest had the upper hand. Corp. William Brown of the 9th Indiana Cavalry had been stationed with a small detail on the north side of the fort down the hill in the ravine where Sulphur Creek flows, performing guard duty for the horse corral located there. “Brown’s detail remained with the horses until a Confederate shell landed about 15 feet from them, and as he said, “tore a hole in the ground large enough to bury a small cow, and threw dirt all over us.”47 The horses were abandoned and the detail scrambled up the steep hill and into the fort. Brown had to cross the center of the fort to get to the east wall in what he called “the most dangerous trip I ever experienced in my life.”48 With Union troops in the fort enduring the Confederate bombardment, Buford ordered his dismounted troops forward across the valley floor, coming from the western elevation where Walton’s guns were firing from. The objective was to reach the western side of the railroad embankment under the guns of the fort. Under cover of Walton’s artillery fire, Buford’s command moved forward with part of Kelly’s brigade and crossed the exposed position to a more protected spot along the railroad embankment and began firing at the fort.49 The artillery inside the fort was not idle and fought with determination, but the two 12-pound Howitzers were outmatched by Morton’s rifled guns, which were firing from multiple directions. Though they responded vigorously, a shell from Morton’s Battery struck one of the cannons, overturning it and killing five men. The other cannon was soon disabled by a shot planted squarely in its mouth. 50 The plight of the U.S.C.T and both cavalry units inside the fort were no better than their counterparts servicing the Union artillery.

The Confederate artillery fire began to take effect; every shell fell and exploded within the Federal work, whose faces, swept in great part by an enfilading fire, gave little or no shelter to the garrison, who were to be seen fleeing alternatively from side to side, vainly seeking cover. Many found it, as they hoped, within some wooden buildings in the redoubt, but shot and shell crushing and tearing through these feeble barriers, either set them on fire or leveled them to the ground, killing and wounding their inmates, and adding to the wild and helpless confusion of the enemy, who, though making, meanwhile, no proffer to surrender, had nevertheless, become utterly impotent for defense.51

Inside the fort, Lathrop, commander of the garrison, had been killed soon after the battle began and command passed to Maj. Eli Lilly (Figure 22). Both of his artillery pieces were knocked out of action and his cavalrymen were running out of ammunition. Soon the Unionist Tennesseans were out of ammunition; for two hours, in desperation, they whittled Springfield musket balls to fit their carbines.52

Forrest was no doubt watching the effect of his artillery from some advantageous point in the area and would have noticed that fire from the fort had slackened significantly. “Seeing their situation, and desiring to put a stop to the slaughter, Forrest ordering a cessation of hostilities, again demanded capitulation. This time, the demand was promptly acceded to, and the capitulation of the blockhouses, as well as the redoubt, was speedily accomplished through proper staff officers.”53

Once the area was secured, the soldiers of the 111th U.S.C.T, 3rd Tennessee Unionist and 9th Indiana Cavalry must have wondered what their fate would be. Early in the afternoon the remnants of the garrison companies were ordered in line, stacked their arms, and after burying their dead comrades and taking care of those who were wounded, were made prisoners of war.54

Confederate soldiers walking around the interior of the fort after the battle were appalled by what they saw. “One of Forrest’s soldiers later recalled, ‘I saw no more horrid spectacle during the war than the one which the interior of that fort presented. If a cyclone had struck the place the damage could hardly have been worse.”55

The night of September 25 was spent in collecting and caring for the wounded on both sides and cutting down and burning the long trestle along with the blockhouses.56

The Union losses in this battle were significant and further helped supply provisions for Forrest’s men. At least 200 federal officers and men were killed inside the fort, while 820 officers and men surrendered. Forrest also gained two pieces of artillery, 20 wagons and teams, about 350 cavalry horses, and a large quantity of ordnance and commissary stores.57

Forrest moved his troopers north along the railroad and reunited with the other part of his force, which had been sent to block any Union reinforcements sent to relieve the Sulphur Creek Trestle garrison. The rendezvous was made at Richland Creek and the march towards Pulaski continued with his command now numbering about 3,300 men who were well supplied and mounted.61 Pulaski was the headquarters for Starkweather’s brigade and he had been gathering reinforcements to attack Forrest south of the town. While Forrest and his command spent September 27 on the destruction of deserted Federal strongpoints along the railroad, as well as the destruction of two more trestle bridges, he kept moving his force north. Early on September 27 Forrest ran into the 6,000 Union troops belonging to Starkweather and Spalding. Again breaking with the official rulebook concerning tactics, Forrest chose to charge a Union force almost twice his size, which was holding the high ground in front of him. Forrest dismounted Buford’s and Johnson’s small brigades across the road parallel to the larger Federal force and sent Kelly’s brigade, still mounted, to the eastward to gain the Federal rear while deploying Morton’s artillery in a forward position in the battle line.62 The larger Union force was attacked from different directions simultaneously and began to fall back towards Pulaski, although turning to fight along the way. “The Union force fell back gradually, and retired within the heavy fortifications at Pulaski. Forrest soon realized that these were too heavy to be carried by storm; so that night he had his men built a long line of campfires; then about ten o’clock withdrew quietly in the direction of Fayetteville and the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad, Sherman’s main supply line.”63 From this line of march towards the east it is apparent that Forrest intended to knock both railroads out of commission. However, time was not on Forrest’s side as he began moving his force towards Fayetteville on September 28. The battle south of Pulaski was to be the last large scale engagement between Union and Confederate forces during the raid. Reaching Fayetteville that same day and destroying the telegraph equipment located there, Forrest then ordered his command toward Tullahoma. However, 15 miles outside of town, scouts brought him information that the Pulaski garrison was moving to confront him.64 These were not the only troops trying to locate Forrest’s command. Scouts also soon reported that heavy columns of Union forces were converging on him from every direction.65 It was during this time that Forrest quickly decided to split his smaller force in half, sending Morton’s remaining artillery back with one column going south back into Alabama. Forrest traveled north with the other column towards Columbia. Morton’s artillery, travelling toward Huntsville in the southern column, was completely out of ammunition after the battle south of Pulaski. “As this place [Huntsville] was approached scouts and citizens brought word that it was strongly garrisoned, and that General Steedman was moving in that direction with 8,000 infantry to prevent the Confederates, 1,500 in number, from crossing the river. The attempt was abandoned, therefore, and the route of march changed toward Newport, where it was known that there were small ferryboats.”66 After crossing the river at Newport, this portion of Forrest’s command made their way back to Florence. Meanwhile, Forrest moved toward Columbia, reaching Spring Hill on October 1, where the telegraph office was captured by surprise. Forrest was able to learn the whereabouts of all the Union forces surrounding him and then used the telegraph office to send false information about his movement in every direction.67 With this activity concluded, Forrest then moved his command south through Lawrenceburg, arriving at Florence on October 5. In Florence, he found that Buford’s command, with Morton’s battery, had already crossed the Tennessee River 36 hours ahead of him.68 With this accomplished, and as Union forces were closing in from behind, Forrest’s command was reunited and began moving back toward the railhead at Cherokee.

From a tactical perspective, the north Alabama and middle Tennessee raid was probably one of the most successful of the entire war. Forrest and his men traveled more than 500 miles, captured 3,500 prisoners, eight pieces of artillery, 900 head of beef cattle, 100 wagons, 3000 small arms along with unusually large stores of commissary, ordnance, and medical supplies.69 Only the Johnsonville raid that Forrest commanded in later October and November 1864 can match the raid into north Alabama and middle Tennessee. Forrest’s loss during the raid, lasting for 15 days, was 47 killed and 293 wounded. Despite these losses, his force had destroyed six large truss bridges, nearly 100 miles of track, two locomotives and 50 freight cars.70 This raid effectively knocked the Nashville & Decatur railroad out of the war as a means for Sherman to supply his army in Georgia, making the victory at Sulphur Creek Trestle an important part of the decision Sherman made to live off the land as his army marched towards Savannah in November. For soldiers belonging to the 110th (which had been captured in Athens), 111th U.S.C.T, 9th Indiana and 3rd Tennessee (Union) regiments, the rest of the war was spent at hard labor and prisoner of war camps. Brown, of the 9th Indiana, along with the rest of the POW’s from the other three regiments arrived at Cherokee, Alabama, on or about September 26, where they stayed for about two days. Then all of the soldiers captured defending the fort at Sulphur Creek Trestle and at Athens were placed aboard two trains of boxcars and taken to Meridian, Mississippi.71 . It was during this time that all of the officers belonging to the 110th and 111th U.S.C.T. were grouped together and sent to a prison camp in Alabama. The U.S.C.T. troops were sent to Mobile to build fortifications around the city while the white officers and enlisted men were imprisoned at Castle Morgan Prison at Cahaba near Selma, Alabama.72

While it would be speculation to say what would have happened with regards to Atlanta had the Confederacy applied more pressure to Sherman’s railroad supply lines in the summer of 1864, Forrest proved during this raid and another one the following month how vulnerable the Union really was. “It was one of the strangest anomalies of the entire war that Sherman won in Georgia by losing five battles in north Mississippi and north Alabama. But those failures, added together, made one grand Union success, because they neutralized the powers of the most dangerous cavalry leader in the entire Confederacy.”73 Sherman’s decision to march through Georgia was based in part by the fact that he thought the war could be brought to an end quicker by doing so instead of chasing Hood around the interior of the western Confederacy. While the Forrest raid was significant, it happened too late to affect the nature of Sherman’s decision-making during the Atlanta Campaign, though it did impact his actions as he continued on his way to Savannah.

Criteria D: Archeology

Archeology examination of the Sulphur Creek Trestle Battle Site has the potential to reveal more information about the events of the evening prior to the battle and the day of the battle itself. While reports about the battle provide historians with a great deal of information, there are points in the narrative of the events of the battle that could be understood more completely as a result of archeological examination. For example, archeological examination could reveal the exact location of Forrest’s campsite on the night of September 24, 1864. Examination could reveal more information about the movement of Forrest’s men as they closed in on the fort site as accounts differ as to the exact route Forrest’s men took. Some accounts place an additional group of Forrest’s men to the north of the fort on another hillside, though official reports do not. Examination could reveal whether men were in fact placed there. As is typical with battlefield archeology, an examination can also reveal much about the men who fought and died in the battle of Sulphur Creek Trestle. Personal effects, including buttons and medals, the remains of camp sites and pieces of equipment all have the potential to be discovered through a close examination of the site.

1 Norman R. Denny, “The Devil’s Navy,” Civil War Times Illustrated Vol. 35 No. 4 (August 1996): 25.

2 Thomas Lawerence Connelly, Autumn of Glory: the Army of Tennessee, 1862-1865. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State Univ. Pres 1971), 436.

3 Connelly, 436.

4 Robert Dunnavant, The Railroad War: N.B. Forrest's 1864 Raid through Northern Alabama and Middle Tennessee (Athens, Ala.: Pea Ridge Press), 199441.

5 Ibid., 20.

6 Thomas V. Ress, “Five Hours at Sulphur Trestle Fort,” Alabama Heritage No. 88 (Spring 2008): 18.

7 Dunnavant, 20.

8 Ibid., 21.

9 Denny, 25.

10 Ibid., 42.

11 Jonathan Sutherland, African Americans at War: An Encyclopedia, 21

12 Dunnavant, 43.

13 Ibid., 43.

14 Ibid., 44.

15 Connelly, 378.

16 Ibid., 377.

17 Ibid., 379.

18 Cornelia and Jack Weller, “Bedford Forrest’s Infantry,” Confederate Veteran (September-October 1991): 32.

19 Thomas Jordan & J.P. Pryor, The Campaigns of Lieutenant General N. B. Forrest, and of Forrest's Cavalry, 2nd ed. (Dayton:American Society for Training & Development, 1995), 556.

20 Connelly, 477.

21 Dunnavant, 14.

22 Ibid., 14.

23 Ibid., 15.

24 Ibid., 15.

25 John Watson Morton, The Artillery of Nathan Bedford Forrest's Cavalry (San Bernardino: Create Space Independent Publishing Platform,2012), 222.

26 Jordan & Pryor, 556-557.

27 Ibid., 559.

28 Ibid., 561.

29 Ibid., 52.

30 Donald H. Steenburn, “A Tale of Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Attack at Sulphur Branch Trestle Alabama,” Blue & Gray Magazine No. 9 (June 1992): 32.

31 Jordan & Pryor, 565.

32 Ibid., 565.

33 Ibid., 566.

34 Ibid., 566.

35 Ibid., 20.

36 Jordan & Pryor, 567.

37 Ibid., 567.

38 Ibid., 567.

39 Ress, 21.

40 Jordan & Pryor, 568.

41Morton, 233.

42 Jordon & Pryor, 568.

43 Ibid., 568.

44 Morton, 233.

45 Both of these steel cast 3” Ordnance rifles manufactured by the Singer-Nimick foundry, are now at Chickamauga-Chattanooga National Battlefield Park where they were placed by John W. Morton in 1890.

46 Jordan & Pryor, 568.

47 Steenburn, 32

48 Ibid., 32.

49 Morton, 233.

50 Jordan & Pryor, 569.

51 Ibid., 569.

52 Steenburn, 33.

53 Jordan & Pryor, 569.

54 Steenburn, 33.

55 Resss, 23.

56 Morton, 236.

57 Jordan & Pryor, 570.

58 Ibid., 336.

59 Ibid., 336.

60 Ibid., 336.

61 Morton, 239.

62 Jordan & Pryor, 572.

63 Lytle, 335.

64 Morton, 239-240.

65 Lytle, 336.

66 Morton, 241.

67 Lytle, 338.

68 Ibid., 338.

69 Ibid., 342.

70 Morton, 244.

71. Steenburn, 41.

72 Ress, 23.

73 Andrew Nelson Lytle, Bedford Forrest and His Critter Company (Lanham, MD: J.S. Sanders Books, 1993), 342.